The Missing Fairies of Norfolk: Part Six

Bronze Age Round Barrows, ‘missing‘ fairies and a side of land enclosure.

Way back in January I boldly stated thus:

My first field of investigation involves a Bronze Age round barrow, the enclosure act of 1807 and the missing fairies of Norfolk. I will endeavour to return with my findings promptly!

Little did I know, that the above statement would lead me down an extremely long and fascinating rabbit hole that would take me until the first week of June to research and finally sit down to write about the aforementioned round barrow. It would seem that promptness is not my strong point.

I did get around to the inception of Norfolk land enclosure in the last instalment: ‘Missing Fairies of Norfolk: Part Five’. And I’ve now neatly linked all parts together on one page of my publication if you fancy a peruse:

So, finally: Bronze Age Round Barrows, missing fairies and a side of land enclosure.

What are Bronze Age barrows? For a brief definition I have turned to professionals who can tell you much more succinctly and expertly than I:

“The main period of round barrow construction occurred between about 4000 and 3500 years ago.”1

Quoted in the EDP Barbara Bender, emeritus professor of heritage anthropology at University College London, states:

"At a time when people were moving around the landscape, herding animals, but also still very dependent on hunting and gathering, they began to mark that landscape.

On the one hand, there were hilltop enclosures, which seem to have been meeting places, places for feasting and rituals. On the other, they built long mounds, often set close to well-known, well-worn ridgeway paths.

They may have served to mark the territories used by herding communities and they may have been ancestral places - the places of the old ones.

This 'mounding' is really only the beginning of the barrow tale - it would be made bigger, re-shaped with more graves inserted into the hillock; even over periods of decades or centuries.

This is significant as it shows burial sites were remembered long after they were originally created; men, women, children interred at different times and probably with different rites and rituals.”2

Barrows then (long and round) were places of importance to our ancestors of the long forgotten past, places of ritual, remembrance and community. For centuries people gathered in these places and they were sacred.

For a fair few centuries after the original builders of the barrows had been replaced by conquestors from other lands their sacred places were still honoured and respected. The name they were given:

“Moot mounds; From at least the 10th century - and perhaps even earlier - East Anglia (like many other areas) was divided into Hundreds, areas of land possibly based on a hundred 'hides' or family holdings. In medieval times, the Hundred was the basis of all public administration, and its courts, known as 'moots' or 'things', and which were second only to the county, were often held at local landmarks such as fords, lakes, prominent boulders and trees - or in these cases, at artificial mounds or earthworks. Moots were also held for other local assemblies such as sheriff's courts, manorial courts, and possibly also for trading or religious gatherings.”3

Often, in agricultural areas, large scale meetings (or Moots) took place out in the open at ‘Moot mounds’ although unclear from the sources I have found online I hazard a guess that the earthworks mentioned are the barrows of yore. Not used for their original purpose of ritual and remembrance, but importance was lent to them nevertheless, adding to millennia’s worth of energy expended in those locations.

The above excerpt refers to medieval times and I surmise that the author means pre-Norman Conquest. When the Norman’s arrived they quickly began building wooden motte and bailey castles all over the shop and I believe administrative meetings (over a few generations) would have been transferred to the Norman’s (from the Saxon’s) and into their buildings. If a “proper” historian of the era could confirm or deny my supposition I would be most grateful!

Therefore, if my musings are somewhat correct, it would appear that after the Norman invasion the people of England began to forget their ancient sacred spaces as they fell out of use (and in many cases reach due to enclosures). In Scotland, Wales, Ireland and perhaps even the West of England where the Celtic peoples held out the longest the folk memory of these places was retained.

I’ll now turn my focus to East Anglia as that is where I can reside and thus have commenced my fieldwork.

“In Norfolk, there are known to be approaching 2,000 burial mounds or barrows, nestling into the countryside.

Many more have been obliterated, ploughed into the landscape, converted for crop cultivation, flattened by wind, rain and time, forgotten. 4

“Few barrows survive in an undamaged state. Far greater numbers have been partly or completely levelled by over two thousand years of agriculture and now appear merely as shallow swellings on the ground surface, or are visible from the air as soil or vegetation marls that indicate the position of buried mounds. Almost every parish contains at least one and often more.”5

Now let us compare this state of affairs with our neighbours to the north:

‘Fairies stop developers bulldozers in their tracks’ - The Times, 21/11/2005.

Locals of St Fillian’s, Perthshire were objecting to:

‘a developer breaking ground for some houses. Why? An ancient rock covering the entrance to a fairy fort.’

Locals feared that moving it would cause upset to the fairies who may then take their revenge. The chairman of the local council was quoted saying:

‘I believe in fairies, but I can’t be sure they live under that rock.’

The times noted that the chairman felt that:

‘the rock had historical and sacred importance because it was connected to the Picts & their Kings had been crowned there.’

I found this incident mentioned in the introduction written by Marina Warner of Robert Kirk’s recently re-published ‘The Secret Commonwealth’. The Scottish builders were stopped because of the folk memory of the fairies. And similar stories can be found relating to road building in Ireland.

So, what secrets do these sacred spaces of old conceal?

Writing in the seventeenth century Scottish Highlands in his posthumously published work ‘The Secret Commonwealth’ Robert Kirk stated:

There be many Places called Fairie-hills, which the Mountain People think impious and dangerous to peel or discover, by taking Earth or Wood from them; superstitiously believing the Souls of their Predecessors to dwell there. And for that End (say they) a Mote or Mount was dedicated beside every Church-yard to receive the Souls till their adjacent Bodies arise, and so become as a Fairie-hill; they useing Bodies of Air when called Abroad.”

And in ‘Explore Fairy Traditions’ by Jeremy Harte

Fairies are not real as the things of this world are real. They live in grassy mounds, but if you slice the top off a mound, you will not find the fairies inside – though you may soon find out that you should have left well alone.

Why is it then that the fairies live in the ancient mounds of Scotland & Ireland but are rarely mentioned in England?

Is it that the retained folk memory of a landscape unrestricted by enclosures allows the connection between humans and something else to remain alive? In Norfolk, (and other parts of England) the land enclosure, that began with a vengeance at the time of the reformation, cut off access and community with what had always been there. Much was forgotten and subsequently destroyed.

But has it all disappeared? Time for some more fieldwork: as Historic England states, “Almost every parish contains at least one [barrow] and often more.” I set out to discover my local tumulus.

A bit of digging online led me to this discovery on the website hiddenea.com:

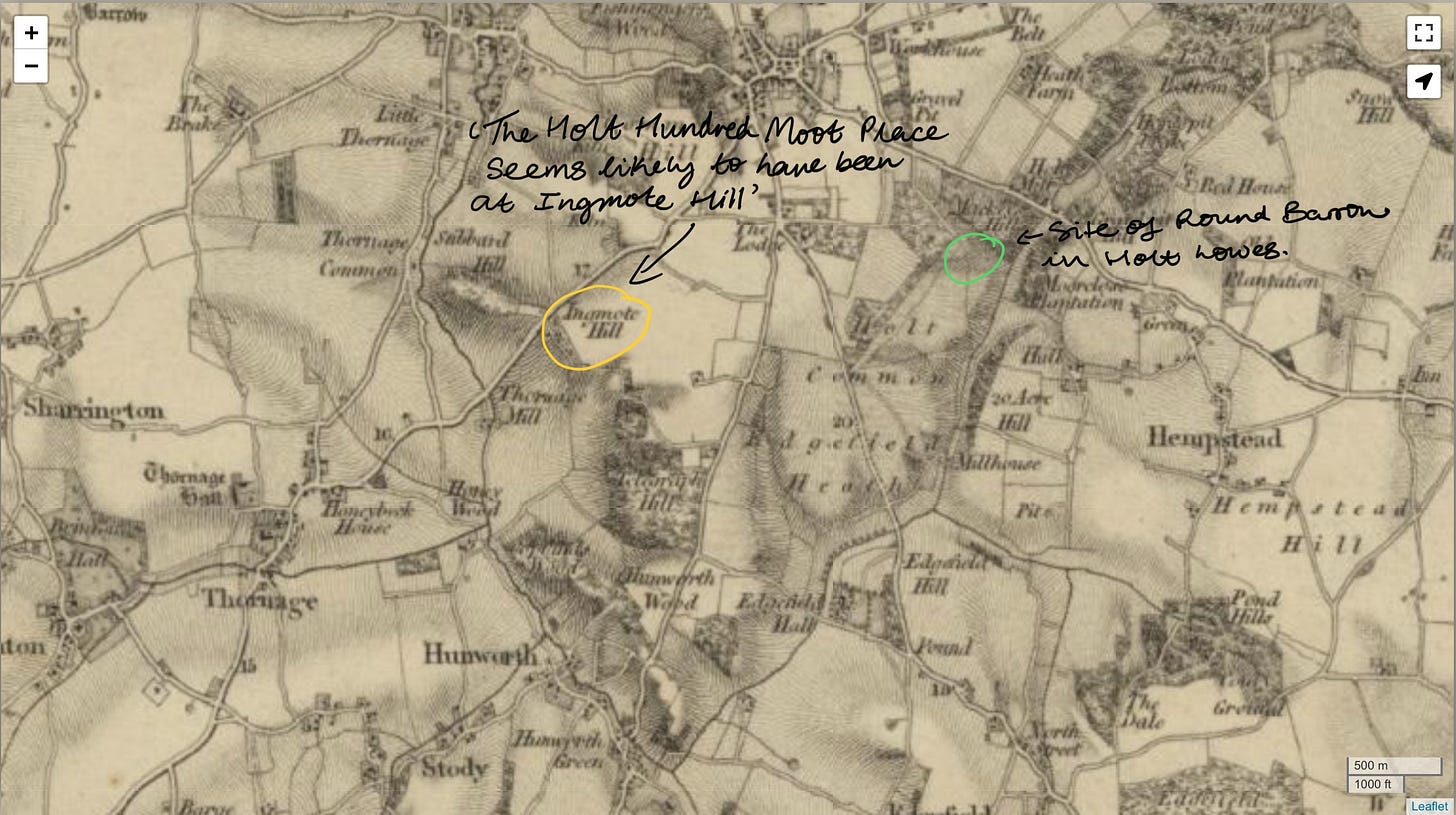

“Holt, Norfolk: The Holt Hundred moot place seems likely to have been at Ingmote Hill, a steep hill overlooking the Glaven valley, south-west of the town.1 Tom Williamson has suggested that there may actually have been an ancient barrow on this height that served as the moot, rather than simply the hill.2 The field-name of Thinghou - 'meeting hill' - is also known in the parish of Holt from a source of 1203, but whether or not it was at or near Ingmote Hill, I don't know.3

Sources:

1. Walter Rye: 'Scandinavian Names in Norfolk' (2nd edition, 1920), p.25.

2. Tom Williamson: 'The Origins of Norfolk' (Manchester University Press, 1993), p.129.

3. Karl Inge Sandred: 'The Place-Names of Norfolk' (English Place-Name Society, 2002), part 3, p.111.”

Unfortunately the locations mentioned above are now on private farm land (our old friend enclosure rearing his head) so I could not pay Ingmote Hill a visit. I did spend a rather long time looking at google earth and old maps trying to discern something but this proved fruitless. However, I did discover that there was a tumulus located on a pocket of common land very near to the apparent ‘Moot Mound’ (in line with it even) that has never been enclosed and has remained accessible to the public since, as far as I can tell, always!

Holt Lowes is a ‘Poors Allotment’. In 1807 the Holt and Letheringsett Enclosure Act passed through Parliament, allowing the land holdings in these two parishes to be modernised and rationalised. ‘Enclosures’ were commonplace in England in this period, and typically involved the removal of the old common rights, whereby most of the residents of the parish rights to graze animals and cut wood and turf for fuel over large areas of ‘waste’ (in other words, heathland and fen). The ‘waste’ passed into private ownership, but as compensation, the Enclosure Commissioners set aside the very worst areas, in terms of their potential for agriculture, for the use of the poor. Holt Lowes was described in the Award as an allotment for houses of the parish not exceeding £10 per annum (i.e. £10 annual rent), and was to be used by the owners and occupiers of such ancient houses for supplying each of them with common pasture for one head of ‘neat’ (cattle), or for one gelding or mare, and for taking flag, ling, brakes and furze for domestic firing.6

Exhibit A 👇

It is here, on this ‘wasteland’, that wasn’t deemed worth enclosing (thank goodness!) where I found my local round barrow. Heritage Norfolk has a short excerpt about it on their website:

“A Bronze Age round barrow on heathland. It was excavated in 1934, but nothing was found. The barrow was visible again after a heath fire in 1986, being 7 metres in diameter and about 60cm high.

About 76cm (2 1/2 feet) high, 6.4m (7 yards) diameter, no ditch. Excavated by A. Q. Watson and J. E. Sainty. Good Friday 1934. Nothing found. Apparently artificial pit to west.

Square hole sunk in the sentry disclosed thick turf of 30cm (12 inches), closely packed rounded flints 10 to 15cm (4-6 inches); black soil about 20cm (8 inches).”7

On the Good Friday of 1934 it appears that A.Q. Watson and J.E. Sainty had a little jolly to the Lowes to poke around and see what they could find. A whole day for 4000 years worth of history! I do not know anything more about their expedition than what I have quoted above, perhaps they thought a day adequate enough or perhaps something put them off from digging any further…we shall never know!

I went for a walk and found the tumulus marked on the map, it’s rather more difficult than one would think with boots on the ground as one does not have the benefit of a birds eye view! The below images are of, as far as I could tell, the round barrow.

Exhibit B, C & D 👇

What did walking up one of Norfolk’s rather petite hills to find a Bronze Age round barrow gain me? Some healthily exercise?! Well yes, but also a sense of connection to a landscape that has been inhabited by humans (and the good neighbours) for thousands of years, a landscape that thanks to luck and perhaps a sprinkling of unknown forces, has remained pretty much un-altered since the ancestors deemed it sacred. The people may have forgotten but the land remembers.

And…

In the second of my Missing Fairies of Norfolk series I mentioned the elusive Norfolk fairy, the Hyter Sprite, much researched by Ray Loveday for his work ‘Hikey Sprites - The Twilight of a Norfolk Tradition’. On the Ray Loveday (online) Archive one of the recollections he transcribed mentions Holt Lowes:

“Nicky described how his mum would say to him and his brothers - “if you don’t leave Holt Lowes before dark the HYTER SPRITES will get you” He pronounced the word HY’ER missing out the T. The family lived in Letheringsett and Holt-dad odd job man. Happened in 50s. Mum was a Cley girl (her mother too) Nicky thought they were “evil little pixie things”. No idea of appearance.”8

So there we are, hidden deep and teetering on the verge of non-existence, a Norfolk folk memory of (as said Barbara Bender) ‘ancestral places - the places of the old ones.’

All this researching and writing takes me quite a while. If you’d like to support my work but don’t want to commit to a monthly subscription please consider ‘buying me a coffee’ through my Ko-fi page so I can continue to share my findings.

EDP - https://www.edp24.co.uk/news/20745930.forget-ghosts-goblins-fairies---true-story-behind-norfolks-prehistoric-tombs/

https://www.hiddenea.com/mootmounds.htm

EDP - https://www.edp24.co.uk/news/20745930.forget-ghosts-goblins-fairies---true-story-behind-norfolks-prehistoric-tombs/

Ray Loveday Archive

Enjoyed reading this whilst eating my porridge, great research, I think the Norman’s liked building their castles, close to rivers and main roads, controlling both these highways, but they also liked to put them on top of existing structures

The best round barrows I know in Norfolk are the ones beside the Peddars Way just east of Anmer.